Next week marks 20 years since the first Far Cry launched, beginning a series of games known for explosive adventures and captivating villains. For the occasion, we sat down with Far Cry IP director Drew Holmes, who is managing the development of the brand, to discuss the series’ central theme of morality and how it shapes the player experience.

Down the rabbit hole

The Far Cry games have presented players with societies riven by violence and challenged them to survive tyrannical forces and ferocious wildlife. Over the course of the series, players have visited six widely different parts of the world. Whether in the Caribbean or the Himalayas, these societies all have one core element in common: They have no accepted laws. “What is or is not moral has changed,” adds Drew.

The development team doesn’t judge the player’s actions. “We’re an impartial observer. We set up the chessboard and ask: ‘If you found yourself in this situation, what would you do?’”

That notion of choice is a core pillar of the gameplay experience. In Far Cry 4, for instance, the player embodies a protagonist who must spread his mother’s ashes in the Himalayas. At the start of the game, the player is taken hostage by King Pagan, who offers to personally take them where they need to go. Drew continues the scene: “You’re surrounded by a bunch of people with guns, and they’re telling you to just hang out for a second and have a conversation. Are you going to die if you do that? What if you don’t think it’s a good idea?”

If the player decides to stay, Pagan shows them where to leave the ashes and the game ends, but the country remains torn between the dictator’s murderous regime and a brutal resistance movement. If the player decides to escape, they enter a chaotic world, join forces with the rebels, and are able to influence events. “You can either walk away and leave things as they are,” says Drew, “or opt in to the insanity, but then you’ll have to dig yourself out of the hole.”

Havoc and restraint

As the story of each game progresses, players fight not only to survive but also to defeat unjust and ruthless forces, such as a dictatorial regime, a doomsday cult, and a human trafficking ring.

Players can help innocents caught in these conflicts, but the way to do so is often with a knife and gun in hand. And yet, there is no morality metre, no one way that things are supposed to be done; players choose their own approach and make moment-to-moment decisions about what they are willing to compromise. As Drew explains, these missions pose the questions: “If the life of someone you care about is on the line, what are you willing to do? And what does that say about you as a person?”

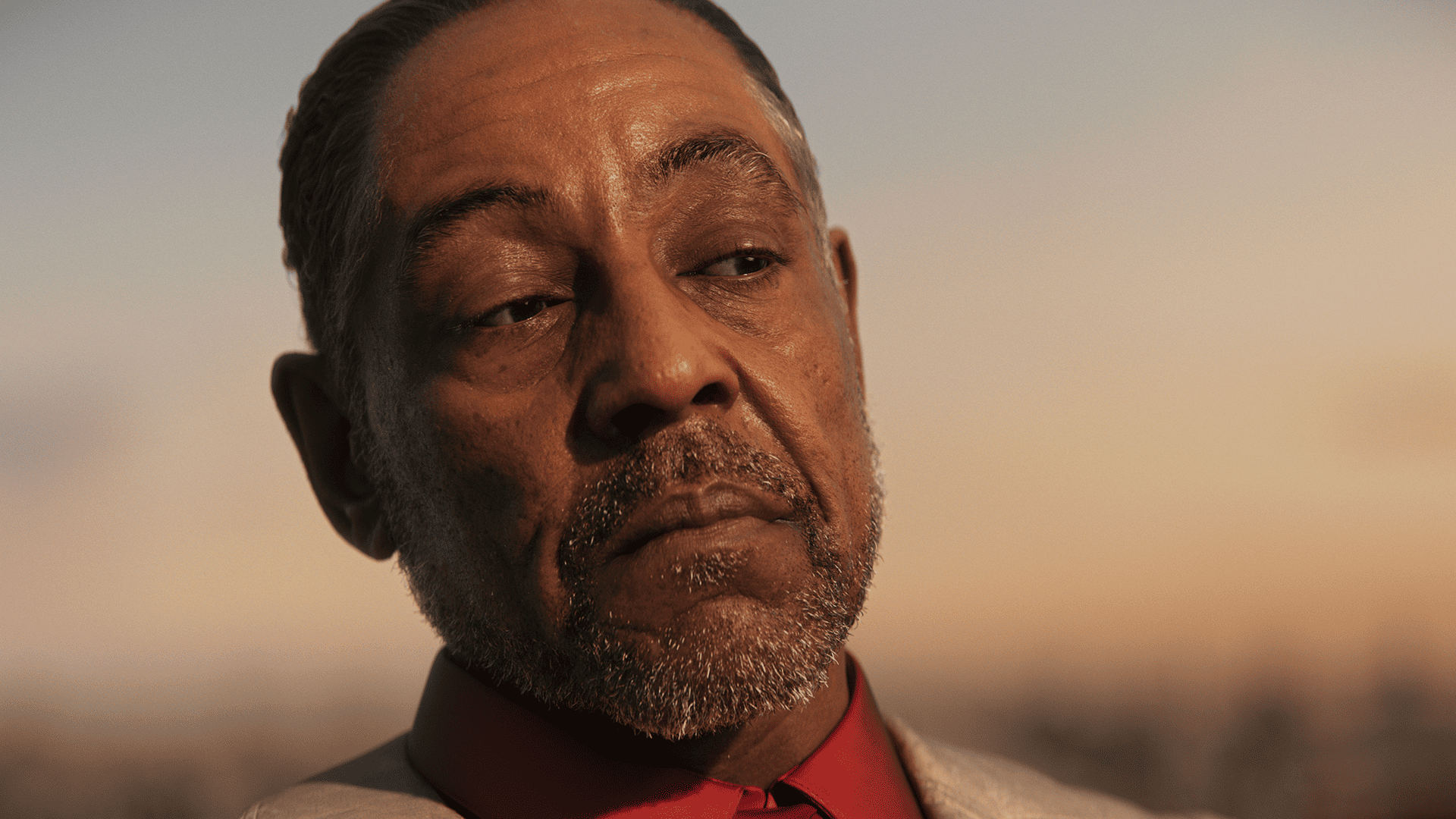

In almost every instalment, the villains attempt to bring the player to their side after having spent most of the game as enemies. In Far Cry 6, the cruel dictator of the region, Antón Castillo, has cancer and wants the player to act as a guardian for his son and shepherd the country after his death.

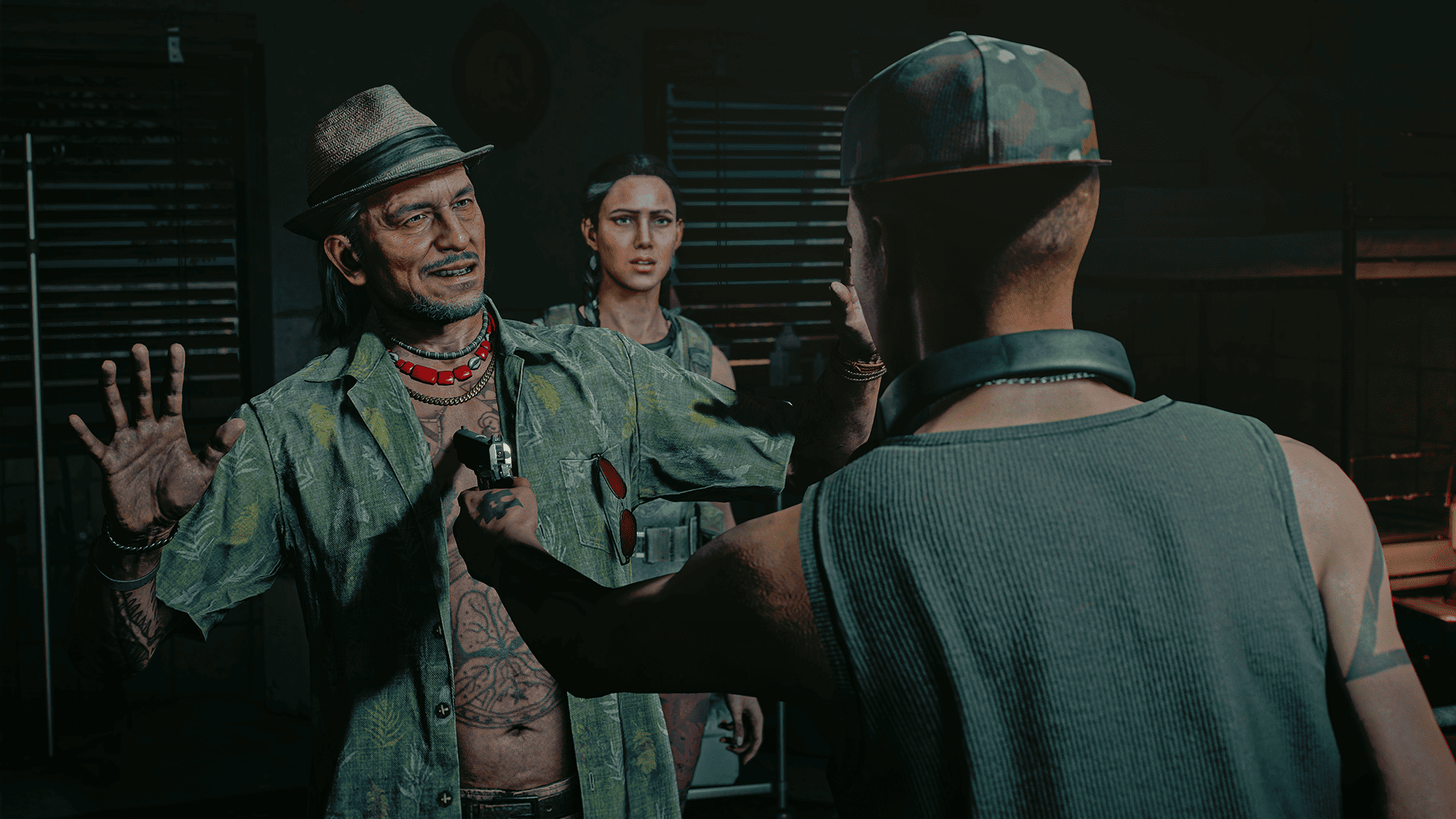

It may seem easy to refuse at first, but the development team makes a point of presenting the villain’s perspective and reasons behind their actions. Drew adds that, “when you look at the fanbase, people love the villains.”

“There’s something alluring about that power and that willingness to go to the extremes to get what you want,” he continues. “Some players may see that the villains are going too far, but also see their point, and think: ‘If I work with them, I can make them see the error of their ways and change them.’”

The situation is further complicated when considering the havoc players can cause in the open world. As Drew explains, the villains offer a seductive argument: “You’ve got all this aggression bottled up, and I don’t care if you let it out. Wouldn’t you like to join me?”

The jungle within

The games don’t attempt to moralize about what players should do, and there are no good or bad endings, just the culmination of their actions. “The feeling you always want to end with in a Far Cry game is a sense of unease,” notes Drew.

In continuing to fight the antagonist, all the woes of the world are not resolved; and in joining them, society does not collapse. “Defeating the bad guy may seem like the thing that you should’ve done,” he continues, “but what are the things that you’ve done along the way to get here? And if you joined the bad guy, is there a glimmer of hope? What happened to the people you met along the way?”

The player’s actions throughout the game are foregrounded during these moments. In Far Cry 3, for example, the priestess of a powerful tribe believes the player to be the reincarnation of a mythical warrior due to their fighting abilities. At the climax of the game, she tries to convince the player not to leave the island with their friends, but instead to complete their journey and embrace a warrior’s life.

By contrasting these two paths, Drew mentions that the game holds a mirror to the player and asks: “Look at the things you’ve done. What do your actions say about what you value?”

The point is to evoke feelings and make space for introspection. “If there’s any common takeaway in the Far Cry experiences,” he continues, “it’s that our primal nature is not quite as far away as we may want to believe. When we’re thrust in wild survival situations, we’re all much closer to becoming the jungle than we may realize.”

In drawing out these reflections, Drew notes that the Far Cry games tackle two fundamental questions: “When we help each other, what is the reason behind it? When we hurt each other, what is the reason behind it?”

Far Cry’s 20th anniversary

To mark this milestone, the Far Cry team will be sharing celebratory content every day next week. On Thursday, March 21, don’t miss the livestream with veteran developers for a look at the brand so far and behind-the-scenes stories. For the latest updates, follow the Far Cry team on X, Instagram, and Facebook.